The perpetual longing for the “good times” may be the bitterest part of adulthood. For some, the pain of the “good times” is the grief of losing childlike simplicity and procrastinating the inevitable change that burns the skin to its finest leather. The moment you realize a beautiful epoch is gone, as they swiftly pass, the “good times” sting like a belligerent bee with a year’s supply of state-of-the-art honey.

Longing for the past isn’t a bad thing until you can no longer move forward. No matter the longevity or recency, reminiscing on the “best time of our lives” will always hurt when we recognize that we attained better times than the current or recent ones. The least that we all want is to exist in the “good times” without fearing their inevitable fleet. Yet, it is the fleet that allows us to identify our memories as anchors for who we become, what we want, and what we hold so dearly that we crumble in their absence.

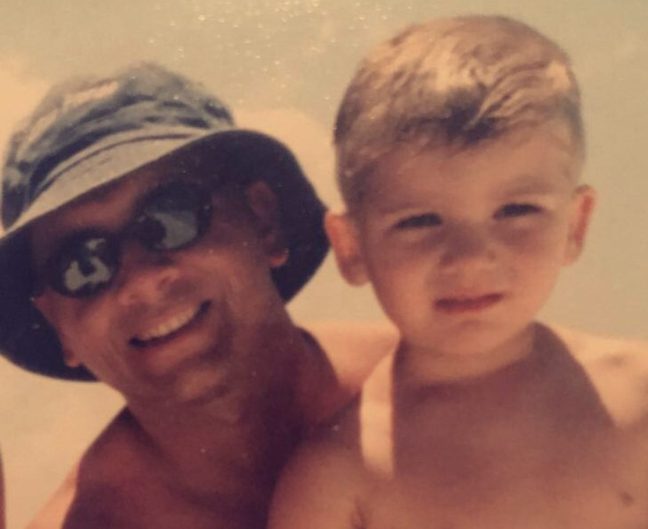

I was roughly seven years old during my “good times.” I would ride with my Dad to get a cheese biscuit every Saturday morning from the fast-food restaurant “Jack’s.” The soundtrack of our weekends consisted of the “80s on 8” radio station and the theme song to the anime show Yu-Gi-Oh! Whenever a 1980s hair band, specifically his favorite, Van Halen, would come on the radio, Dad would sing out of tune and play air guitar as if he sold out Madison Square Garden. Instead, he was driving a vaguely tan Ford F-150 with an audience of one.

Dad loves his music loud. Every single first day of school, the rapidly rumbling drums of Van Halen’s “Hot for Teacher” would roar throughout our town’s highway like a speed-happy Harley Davidson. Once the song concluded and our heart rates had settled, Dad would preach to us about the original lead singer, David Lee Roth, and how he was superior to the more recent vocalist, Sammy Hagar. He acted as if it were a debate we had sustained since 1987. Looking back, I always let out a half-assed chuckle, like I do when I hear a clever joke that doesn’t evoke much reaction. Nonetheless, it was a ritual that remains on my exhaustive list of traditions.

My father is a strong yet expressive man who ensures you are aware of what he loves. Fortunately, I inherited the same traits. I started learning to play the ukulele when I was 14 years old. Financially, it was a low-risk investment, but it proved to be a high reward for me. One night in December of 2013, when Alabama winters felt less like an Ohio spring, my Dad walked into my room and asked if I could learn a song for him. The song was by Skid Row, a band with no business for a ukulele.

I scavenged the fretboard for answers to the correct notes and solved the song’s puzzle when the chorus crept up. I will never forget him chuckling and saying, “Dude, we have to get you a guitar.” I thought he was blowing smoke, but until it happened, it was all I could think about.

I got a cherry-red Squier Stratocaster and a puny Fender amplifier on my fifteenth birthday. The first song I began learning was “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” by Jimi Hendrix. It was ridiculous to assume I could master it without prior experience playing the guitar, but you have to capitalize on the opportunities exciting your Dad. My initial focus was the blues and psychedelic rock at the time. Any tune by guitar legends like Hendrix, Eric Clapton, B.B. King, or Stevie Ray Vaughan would send shivers down my slightly curved spine. I never mastered any songs by those guys, but I never put down the guitar.

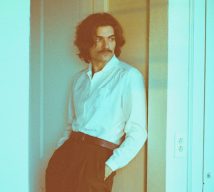

Ten years later, I am still far from a virtuoso. I’ve just told myself that I’ve improved in my own unique way. Most of my time practicing was spent learning songs, which lasted roughly five hours daily. I never took lessons because I broke into sweats at the thought of paying an unbearably average-looking white guy with a ponytail to tell me what to do. It seemed like a scam. Once the skill came to me, I learned blues scales and played along to John Mayer and Grateful Dead live recordings. My original goal was to become what guitar snobs consider “a shredder,” where a guitarist will extend a three-minute song to 12 minutes of improvisation. I got pretty damn good.

However, I began listening to music that was less about impressive musicianship and more about artistic value. That John Mayer guitar prodigy mentality never seemed to fade, but I became increasingly concerned with identity and writing songs as pieces of a bigger picture. At first, it was a juvenile process using GarageBand to record my ideas. Ironically, I frequently worked on ambient music rather than my roots, and it sounds much more impressive than it was.

It took me roughly two years after I started practicing guitar to begin writing music intentionally. My first song was called “47.” I wrote it on the balcony of a beach condominium in the Summer of 2016. It was an acoustic song about my girlfriend at the time because what else would a moody teenager with a guitar write about? I purchased a microphone, recorded it on the free audio software “Audacity,” and posted it online. In retrospect, “47” was pure, unadulterated garbage, but I’m thankful it exists because I never stopped writing from that moment forward. Thus, I became insistent on making music my full-time career.

Like most art forms, I perceive music as a definitive work that often outlives its creator’s dreaded mortality. My single most prominent fear is that whatever I do throughout my life will not endure my physical existence. I crumble at the thought of being forgotten or failing to fill the role of being the person who lives in other people’s fondest memories. The letters and poems I write for my mom, my library of journals, and my music became my product-based approach to metaphysics. It’s an immortalizing approach and severely unreasonable, but the pressure felt natural.

However, by the example of my beloved Nana, each passing day reveals that my notion of escaping oblivion through my work is irrational. It’s about the love, the memories, the time, and the sacrifices we make for those dearest to us.

My Nana, also my role model, once gave me more money for my birthday than I expected. I told her she didn’t have to do that, and she replied, “Of course I did. I have to give it all to y’all before I’m gone.” There is pure novelty in her desire to ensure her love is known, even if she provides less for herself. Nana was a teacher at a small-town Alabama elementary school that no longer exists. Her petite trailer sits about a mile from her former workplace. She retired over a decade ago but found a job at a mining museum in a dusty, poorly-lit high school gymnasium. By July of every year, she has finished roughly 75 percent of her Christmas shopping, including what she calls the “overflow bag.” This was a concept she came up with when she realized she wanted to give everyone an excessive amount of gifts in addition to our original requests. She typically gets me musical knick-knacks.

Nana lives a simple life. It’s a life revolving around the people she loves. Her finances are guided by how much she can give to everyone else, and her radiant smile merely reflects ours.

Antonymous to Nana, a couple of years ago, I finished Christmas shopping approximately one week before Christmas day. The only person I had yet to buy for was my father, but I only had about ten dollars in my bank account for the next week. Business was scarce at work, so money wasn’t necessarily my claim to fame. We creatives tend to put ourselves in torturous situations where we must improvise.

My two options were to either make my Dad a gift out of crafts or buy him a redundant Alabama coffee mug. I created a home studio out of a utility closet in my one-bedroom apartment in Birmingham. Being the professional I wished I was, I began learning the chords to “Jump” by Van Halen. I recorded and produced a full cover of the song, making the instrumentation the focal point rather than my vocals out of insecurity.

On Christmas Eve night, I recorded the guitar solo with my best Eddie Van Halen impression. Dad always loved it when I played Eddie’s tapping technique on the guitar, which was far outside my wheelhouse. I played the recording for my mom on the same bedroom floor where I recorded “47”, and her pearly white smile extended as far as her ears would allow.

My parents opened the gifts from my brother and me on Christmas morning, and my father saw the brand-new AirPods my mother had bought for him. He tends to be technologically challenged, so I used that as an excuse to help him connect them to his phone for a test drive. Luckily, he didn’t notice the ring sound effect when he received the text message I sent, which contained the “Jump” cover audio file.

I hit play. Show time.

His face was illuminated with excitement from my song choice. I nailed the initial synthesizer tone so that he couldn’t distinguish my cover from the original just yet. I observed with the same nervousness I do when I expect a jump scare in horror films. My David Lee Roth impression, more audible than I preferred, faintly mustered through his fresh headphones and signified my entrance to centerstage.

Dad looked at Mom and said, “That’s Cole!” She nodded with a grin as he paced around, blindsided by a gift that was seemingly more valuable to him than Alabama memorabilia. It was quite an intimate scene because he was the only one intently listening, and we allowed him the space to digest it emotionally. While making my third cup of coffee, I fought through his subtle sniffles to see if he had reached the guitar solo. I heard two bends of the high E string, an abruptly syncopated drum fill, and a confusing chord progression, all of which indicated the solo’s arrival.

Once the track faded and my shoulders slackened with relief, Dad eagerly greeted me with misty eyes and the hug of a straight jacket. “This was the best gift I have ever been given,” he said. “Me too,” my mind silently replied.

If only he knew, I would record a whole Van Halen album for him.

My craft’s provision evolved, and my values became more clear. I have blushed and beamed at the sound of shrieks from an audience when I swagger on stage, bolstering my guitar as my lethal weapon. I have seen my work accrue enough success to throw parties that won’t matter the next day once the cake disappears and it’s time to clean up the performative champagne explosion. Instead, I found myself scratching the same gray carpet that clung to my blonde leg hairs during my first attempt at recording music. Those gold-dusted desires I masked as dreams became plain nothings once my father’s tears gradually trickled down his dark, accentuated cheekbones.

It was at that moment that I recalled how Nana teaches us the importance of humility and intention. She teaches us to take care of our own and to do so with a willingness for sacrifice. For Nana, the most prized human connection begins in a vacuum of our kin-folk, where our dreams are less gleeful when we are finally on that grand stage and we can’t see their familiar faces. The world begins and ends with our own blood.

Dad’s ultimate stage was the driver’s seat of that old truck, but the show didn’t go on if me or my brothers weren’t in shotgun. Years later, as each motorcycle passes by my home, I still hear the intro to “Hot for Teacher.” Every Saturday morning, I wake up defibrillated by the thunderous guitars from “Eruption,” as if Dad played it so loud that it continues to echo after all of these years, and I can still grip the memories I’m not willing to cut loose.

As I cruise throughout the bigger city 40 miles from home, I like to think my hometown streets can hear the guitar solos blistering and bourgeoning from my own car, expecting to pass by my Dad.

I don’t have to write music that publications name album of the year. Making music is no longer really about the music. It may be my newfound catalyst to connect with those I love. In hopes of replicating the iridescent joy mastered by Nana and creating the saccharine-soaked memories pioneered by Dad, I now prioritize giving all I have to enrich the lives of those I love. Breathing life into the casual and superficially mundane moments has become more fulfilling than having my own stage, and I want to eternally breathe the same air as those I love the most.

The “good times” have never left. We just change.

When my Dad drives around with my 7-year-old nephew, he asks him if he wants to listen to the Van Halen version of “Jump” or my version. He usually chooses my version. The great debate was over. Van Halen’s best lead singer was neither David Lee Roth nor Sammy Hagar. You can ask my Dad who it is.

This essay is dedicated to the following individuals:

My mother Jean Ellen Manasco – I know it must be difficult to tolerate someone so similar to Dad. No one can do it as well as you.

My grandmother and best friend, Dina Pozak – You are the human embodiment of compassion and joy. Your love and presence guide me morally and remind me that life can be as simple as loving those nearest to you.

Lastly, my father, Greg Manasco – You don’t take yourself too seriously. You hug everyone you meet for the first time because formalities are overrated. You remind me that you are always a call away, no matter the distance. I would not stand as the man I am today without you, and I am eternally grateful to have taken notes from you. Your grandkids will thank you later.

This was an enjoyable slice of life….and Van Hagar sucks!

LikeLiked by 1 person